September 2020 – Dr Charlotte Hoole, LIPSIT Co-Investigator

Originally published on the City REDI Blog

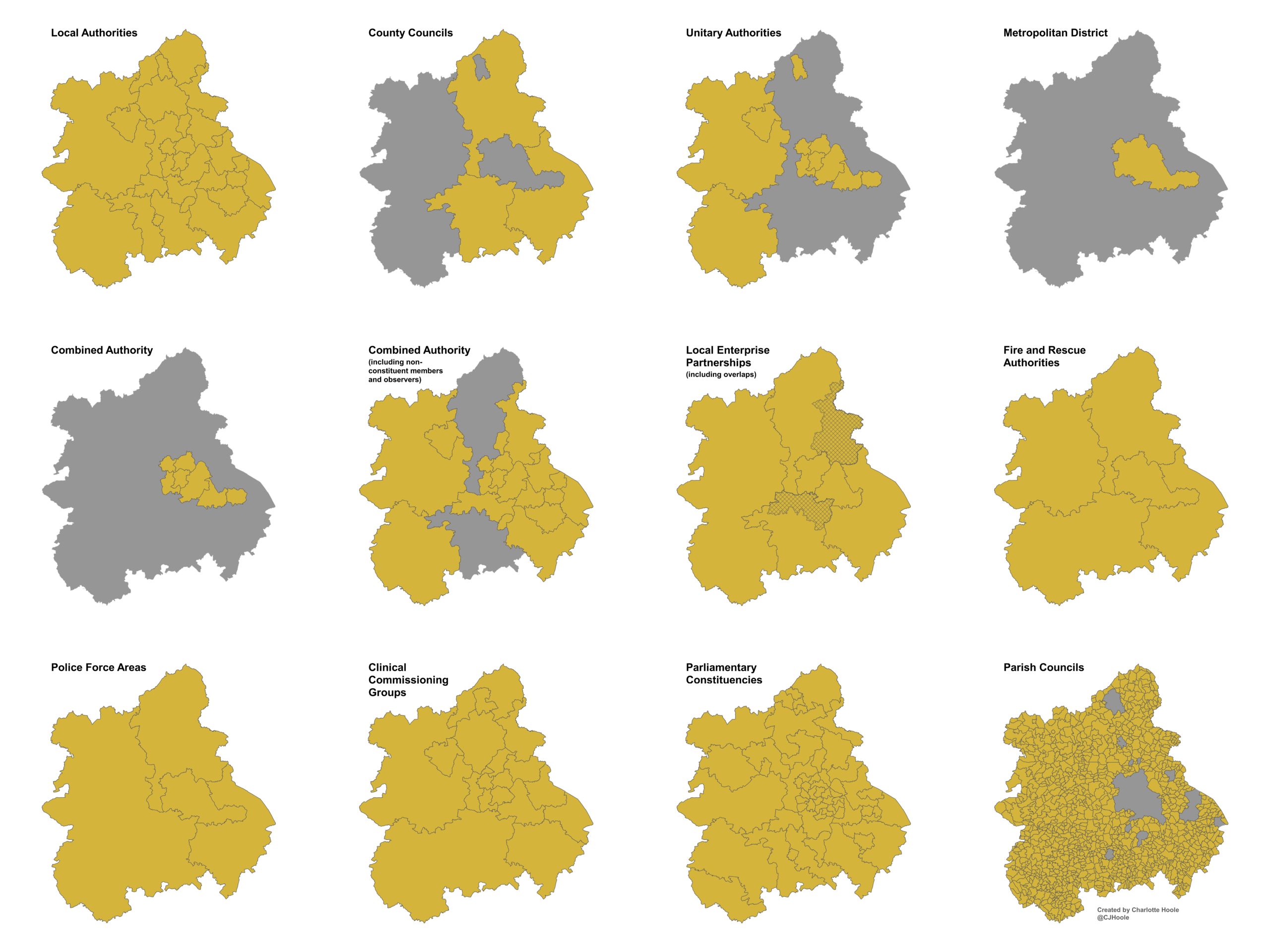

In our latest blog, Dr Charlotte Hoole unpicks the complex world of local government through an in-depth look at the institutional make-up of the West Midlands.

Back in 2006, the then head of communications at the New Local Government Network was quoted in the Guardian as saying “the complexity of local government is something that even councillors can find perplexing and for those on the outside it can seem more puzzling than a Rubik’s cube”. Fast forward over a decade and it would seem that the situation has become even more complicated with the introduction of local enterprise partnerships (LEPs) and, more recently, combined authorities as new regional tiers overlaying already multiple layers of local government institutions that span various administrative boundaries. This institutional landscape has built up over many decades of urban and regional restructuring, with some of the local government institutions we still see today dating back to the late 19th century. This has made it inconsistent and difficult to understand. The structure of local government and the distribution of functions between institutions also vary according to local arrangements. Distinguishing the different geographies and the roles and responsibilities of local versus county councils or combined authorities versus LEPs can be challenging. To shed some light on the matter, in this blog I take a closer look at the institutional make-up of the West Midlands. I have produced a graphic that maps these institutions side-by-side to help understand their size and coverage, as well as (in hopefully a simple way) begin to unravel the complexity of local government.

The West Midlands region (known as a NUTS1 region for statistical purposes) is one of nine official regions in England, made up of 30 local authorities. Each local authority has an elected leader and cabinet and is responsible for a wide range of services, including education, housing, social services, highways and transport, waste management, planning, economic development, environmental health and services, leisure and cultural services, and emergency planning (not just for emptying the bins or filling in pot holes it seems!). Of these, 11 are unitary authorities with a one-tier structure of local government while 19 fall within one of the three West Midlands’ county council areas and have a two-tier structure of local government where public service responsibilities are shared between the two.

In the region we also have the West Midlands metropolitan district (known as a NUTS2 region for statistical purposes – although confusingly it has the same name as its NUTS1 counterpart) that covers seven of the 30 local authorities (or metropolitan boroughs), these are: Birmingham, Coventry, Dudley, Sandwell, Solihull, Walsall and Wolverhampton. Formerly known as the West Midlands County Council area until 1986, the district (together with a number of members and observers within the wider West Midlands geography) is now headed by the West Midlands Combined Authority (WMCA).

The WMCA is a new administrative body created in 2016 for the participating authorities to collaborate and take collective decisions to receive additional powers and funding from government. The WMCA’s main priority areas are economic growth, transport, housing and skills and are led by Mayor Andy Street who was elected in 2017 on a three year term (the 2020 West Midlands mayoral election was postponed to 2021 due to COVID-19). While constituent membership of the WMCA is restricted to the seven metropolitan boroughs that make-up the metropolitan district, non-constituent members of the WMCA (that have less voting rights and can sign up to more than one combined authority) include the Black Country LEP, Coventry and Warwickshire LEP and Greater Birmingham and Solihull LEP together with the following local authorities: Cannock Chase, North Warwickshire, Nuneaton and Bedworth, Redditch, Rugby, Shropshire, Stratford-on-Avon, Tamworth, Telford and Wrekin, and Warwickshire. The WMCA also has a number of observers that are awaiting non-constituent membership, these are: Herefordshire, the Marches LEP, the West Midlands Fire and Rescue Authority and the West Midlands Police and Crime Commissioner.

Additionally, there are six local enterprise partnerships in the West Midlands region (four of which have already been mentioned above in relation to the WMCA). These are: Black Country LEP (BCLEP), Coventry and Warwickshire LEP (CWLEP), Greater Birmingham and Solihull LEP (GBSLEP), the Marches LEP (MLEP), Stoke-on-Trent & Staffordshire LEP (SSLEP) and Worcestershire LEP (WLEP). Set up in 2011 to reflect real, self-defining functional economic areas in the West Midlands region, these are private-sector led partnerships between local authorities and businesses responsible for driving economic growth and creating jobs. A number of local authorities in the West Midlands fall under two LEPs creating overlaps – Lichfield, Tamworth and Cannock Chase are members of GBSLEP and SSLEP while Wyre Forest, Redditch and Bromsgrove are members of GBSLEP and WLEP. This has caused problems in relation to their geography for which, in 2018 the government announced a LEP review in part to “remove overlaps” and “encourage local enterprise partnerships and mayoral combined authorities to move towards coterminous geographies where appropriate”. In the West Midlands, where the region’s only combined authority is uniquely placed in covering a three LEP geography, a solution is yet to be reached.

Other bodies in the West Midlands region include five fire and rescue authorities, four police force areas and 22 clinical commissioning groups responsible for commissioning the majority of hospital and community NHS services. Operating on smaller geographies in the West Midlands are the region’s 59 parliamentary constituencies and (much smaller) 1,096 parish councils. Parliamentary constituencies are districts that elect and are represented by one Member of Parliament in the House of Commons. Parish councils are elected bodies and – as this blog points out – are the closest tier of local government to citizens. Functioning at the community level (the largest in the West Midlands being Sutton Coldfield covering a population of over 75,000), they represent local communities in mainly the region’s towns and rural villages, have certain tax raising powers, and are responsible for local services including: community centres, parks, cemeteries, war memorials and allotments.

In light of the ongoing COVID-19 crisis, the need for concerted local policy efforts and cooperation to make quick, informed decisions has been higher than ever before. The West Midlands has been a good example of such collaboration locally but complex institutional set-ups with variable geographical jurisdictions across England is unlikely to maximise the efficiency of local decision-making. While we await the next potential reorganisation of regional infrastructures in the promised autumn publication of a white paper on devolution committed to “strengthening local institutions” and “removing the complexity of governance”, local government must continue doing their best to work effectively within the current arrangement. Gaining a shared understanding of the division of responsibility between the various local government institutions will be essential in doing so.